Illustration and Authenticity w/ Marcos Chin February 9, 2021

With commissions from giants like Starbucks and Rolling Stone, to his breathtaking and provocative personal work, Marcos Chin is no stranger to the ups and downs of the art world. We had the immense pleasure of speaking with Chin about his incredible body of working, finding his voice as a queer artist, and navigating creative economies.

BLNCD: So as an artist, how has the pandemic and the quarantine been for you? Do you feel more inspired, less inspired?

MC: I wouldn’t say more or less inspired. Things have remained the same in the sense that I usually work alone. I’ve had a studio for most of my career, but up until about two years ago, I started working from home, and so I’m pretty much doing what I used to do. Things like riding on the MTA, on the subway, just those things that maybe seem kind of like moot points, not having that has created a little bit of stress and discomfort, but I don’t think it’s necessarily affected my art making.

BLNCD: You’ve been productive. You started a mentorship program during the pandemic.

MC: I started in September. I’m working with two artists. I think it’s ending somewhere around March, April or May. They’re both very, very different. One of them, Christian, he went to school studying illustration, and he’s since then doing sort of both commercial art and fine art. Then Komikka, she is from an art background, undergraduate/graduate… recently I’ve given her projects in order for her to explore different ways to, I guess … I wouldn’t say improve her technique because she’s such a strong drawer to begin with, but I’ve given her assignments in order for her to try something that’s outside the scope of what she already does as an artist.

BLNCD: Is the mentorship program influenced by your own development as an artist, remembering the kind of support that you would’ve liked to have, or the mentors that really influenced you?

MC: Okay, so I’ve been teaching for 13 years. I’ve been working for 18 years. I have advised graduate students within illustration programs, but this is something new in the sense that, to be completely honest with you, what happened last summer, the protest, the Black Lives Matter movement, all of the turbulence that I think was kind of created by the pandemic. I mean, it’s always been underneath, but it sort of cracked open and became more overt. When all of that spilled out, I think it affected a lot of our lives and it actually bled into or incorporated itself into my teaching space. And there were some controversial things that happened at the school that I teach at where certain people were being accused of being racist, and the school was being accused of not supporting students who were POCs, and there were just a lot of things that were sort of brought into the open. And as a result of that, I started to question the role that I have in the industry as someone who’s been working for as long as I have, and also some of my former students sort of called me out and said, “Marcus, what are you going to do about it? You talk about inclusivity. You talk about sharing information. You just talk and you share in the sort of social media spaces about the things that you care about, so what are you going to do now?” I mean, I feel like I’ve always been supportive and I’ve always tried my best to share and to give information and whatever it is that I know, especially because I come from a working class family and have spent most of my life living a working class person’s life. So they really … I think it was mostly my former students who encouraged me to question the role that I was or wasn’t playing during that time. When I decided to do this mentorship program, it was really a response to the fact that education is just so expensive in America. A lot of students who want to study at these schools just can’t afford to. They, like myself, I come from a family without any generational wealth. My dad worked in a factory. My mom worked in the office. My dad was unemployed since I was 16. My brother and sister and I, we’ve all been working since we were 10 years old, and so we are very self-sufficient in that capacity, and I know how hard it is to want things but not be able to afford it. And so there oftentimes, there are moments where I feel like, “Wow, like I still can’t believe I’m doing what it is that I’m doing.” I created that mentorship program through and posted it on social media specifically to cater to those individuals who come from maybe non-privileged means, who may come from spaces that are often overlooked.

BLNCD: That’s really cool. There’s a lot of really amazing conversations that have been happening around accessibility in the arts community. To take the work that you’re doing as a mentor, as an educator outside of “the institution” is a really cool thing.

MC: But also, when I came to New York years ago, I wanted to go to SVA. I wanted to go, and I knew that I couldn’t afford it. So it’s really sort of ironic that I’m actually teaching here now, and I’m able to share what I know through the school with people who can’t afford to study there.

BLNCD: You have a very clear point of view, a very clear style in your work. When do you remember first honing that point of view?

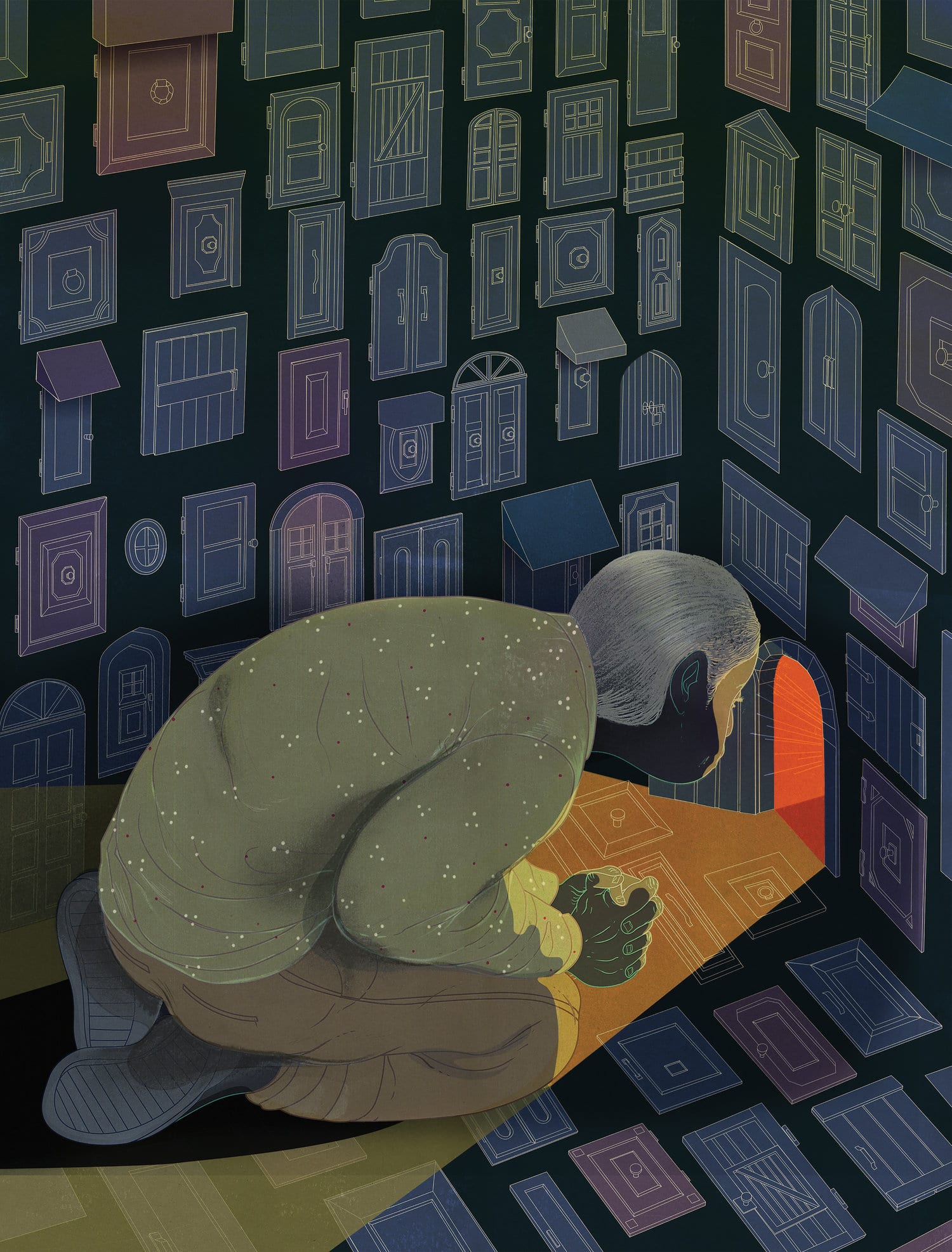

MC: So I moved to New York in 2005. I would say it was when I came to New York when things really started shifting, where I started to give myself permission to have a point of view. Because before that, when I started to work full-time as a freelance illustrator, my entry into the industry had nothing to do with creating work that had any meaning. That wasn’t my intention. It was to enter the fashion lifestyle illustration space to create pictures that would appear in magazines and advertising, so that I could make money so that I could have a better life than the one that I had growing up. That’s all I cared about. I just wanted to try to come to a point where I didn’t have to worry as much about money, and I’m being completely honest with you. That was a huge driving force. And then when I started to financially do better and then moved to New York City, that’s when I started to meet friends and acquaintances and come across heroes and people who have lived in New York or passed through it who started to share their stories with me and helped me realize that making art could be larger than just what it was that I was doing. And so I started to create pictures, I think, that represented my experiences as being a gay man in the industry. I started to tap into more so into my ethnicity and sort of share my stories in that capacity. And not only through drawing, but also through sort of confessional writing, I guess. In addition to being encouraged by those people who I met in New York City, it was also, I think, a response and reaction to being told that it wasn’t something I should be doing. My first agent, when I wanted to include illustrations in my portfolio that reflected the kind of life that I was living in my 20s … I was going to gay clubs, et cetera, they told me to remove it from my portfolio because they thought it would offend clients. They thought it would hurt my business, their business, and so it was kind of like I came out of the closet and then I was sort of put back in. Within the industry that I work in, it’s very cis straight white male, and it’s been like that since the late 1800s. That was how it was in my brain, and I think that was how it was for a lot of people. And so as I was coming up, I felt like I didn’t want to challenge it until I moved here.

BLNCD: It’s funny because that’s what made us want to interview you, because it was so cool to see an artist who’s thriving professionally, but who’s also actively making work that’s unabashedly queer. Not to one dimensionalize you as a queer artist, but it is cool to hear how it intersects with your work.

MC: But I was going to say too, in that time, I was fortunate that I was able to give some talks to students at schools and some sort of art related events, and some things started to change in the mid 00s, mid to late 00s where after my talk, I would have young illustrators come up to me and start to ask me questions and talk and share with me how they wanted to create certain types of work, but they felt like they couldn’t. Talking with those certain young illustrators, young artists, about how they couldn’t show who they were, their queer selves through their work… that made me question, maybe I should think about being more visible through mine.

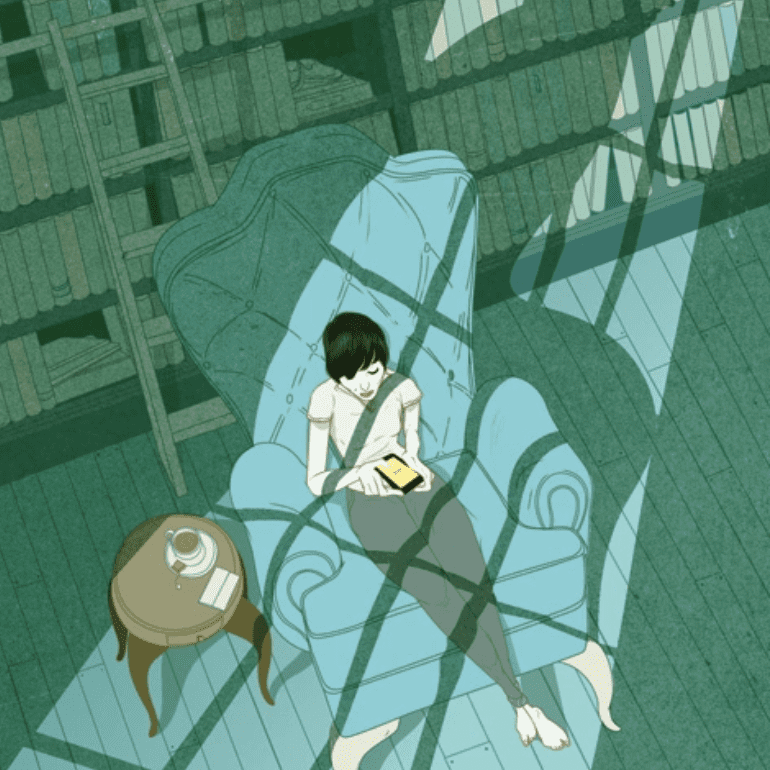

BLNCD: What is your ideal environment for when you’re illustrating? Is there a certain time of day?

MC: Morning. Yeah, morning, alone. By 2:00 I feel very tired. By 5:00, I pretty much can’t do anything, which is weird that I teach in the evening now. But yeah, my most productive time is in the morning, very early. I mean, 6:00 in the morning.

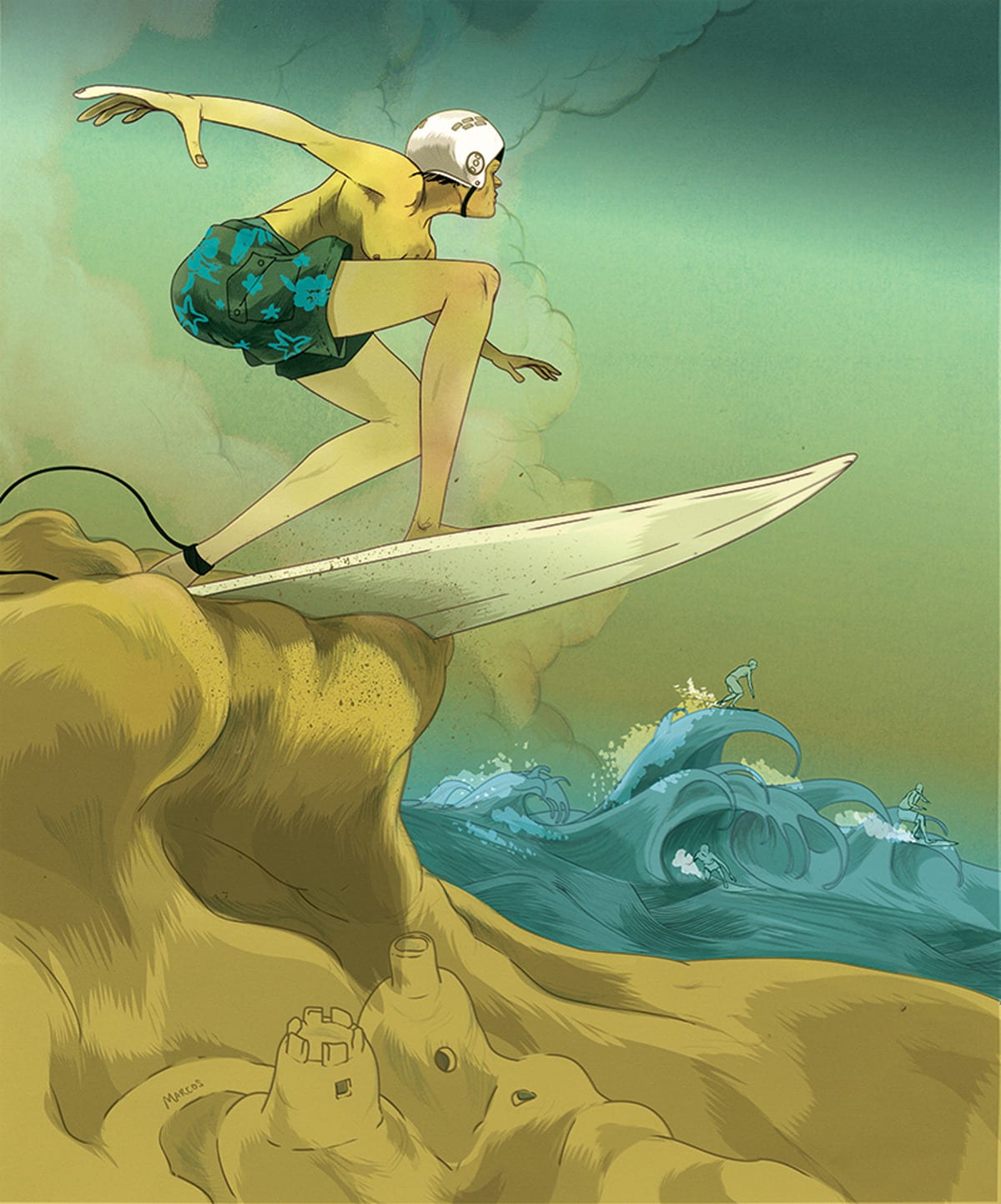

BLNCD: Your art has been able to exist in a lot of different spaces and places. Looking forward to 2021 and beyond, is there anything that feels uncharted for you as a creative?

MC: The summer before the pandemic, my friends and I went to Monterey, California, and we had this kind of end of summer beginning of fall ritual where we announce to each other what we want to leave behind and what we want to bring forward. I remember saying that I wanted uncertainty to be my compass. There’s so much that I don’t know, that I want to do that I believe will still bring me joy through my craft and through my profession, because a lot of the things that I had done previous to this, I didn’t even know that I wanted to do.